Ethiopian women in traditional clothing

Ethiopian women in traditional clothing

My year spent in Israel offered an unexpected glimpse into the rich heritage of Ethiopian Jewish women, particularly their traditions surrounding women’s health and well-being. During a presentation by Ethiopian Israeli women at an Orthodox women’s yeshiva in Jerusalem, I was introduced to the concept of the “menstrual impurity hut,” a practice that resonated deeply with modern ideas of a Seven Day Spa retreat, though in a very different cultural context. This initial encounter sparked a deeper investigation into these traditions and their evolution in contemporary society.

Later, a casual lunch conversation with Israeli students about Leviticus 12:1–5, concerning postpartum impurity, took a personal turn when my Ethiopian Israeli friend, Ahuva, revealed a poignant detail about her mother. Ahuva whispered, “My mother has seven daughters.” Connecting this with the image of a lone woman in the “menstrual impurity hut” from the earlier presentation, I began to understand the profound implications of this tradition. The “menstrual impurity hut,” or beit niddah in Hebrew, was a designated space for women during menstruation and postpartum, a sort of ancient, community-based seven day spa focused on ritual purification and rest.

Ahuva explained that after each daughter’s birth, her mother spent 80 days in the beit niddah. “Seven daughters!” Ahuva emphasized, “and for each, she was alone for 80 days!” While food and water were provided, and the time allowed for bonding with each new baby, the isolation must have been significant. Adding to this, Ahuva’s mother observed a seven-day stay in the beit niddah every month during menstruation, from menarche to menopause. The sheer duration of time spent in this ritual space – nearly a year and a half for postpartum alone, not counting monthly cycles – painted a picture of a life deeply intertwined with these cycles of purification and retreat.

Arriving in Israel in 1991 during Operation Solomon, Ahuva’s community, whose practices were deeply rooted in the Torah, faced a cultural shift as they discovered the absence of the Temple in Jerusalem. While embracing their new home, much of their traditional culture, including the beit niddah, underwent transformation. Ahuva’s story offered a personal window into this complex transition. Her hushed tone suggested both a sense of relief at leaving the beit niddah behind and a lingering sense of connection to this ancestral practice.

Intrigued, I returned to Israel a year later to delve deeper into Ethiopian Jewish purity laws. Through 33 in-depth interviews with Ethiopian women, spiritual leaders (kessim), and rabbis, I sought to understand the traditional practices, their evolution in Israel over the past two decades, and the perspectives of younger religious Ethiopian Israeli women in their twenties and thirties. These women, having experienced childhoods in Ethiopia and then migrated to Israel, offered unique insights into reconciling tradition with modernity. My focus was particularly drawn to how women like Ahuva navigated their religious lives in Israel, considering their cultural heritage.

To grasp the perspectives of these younger women, conversations with their mothers and grandmothers were essential. Over homemade injera and coffee, these intergenerational dialogues revealed the intricacies of the beit niddah tradition. In every Ethiopian Jewish village, at least one beit niddah served as a seven day spa-like retreat for menstruating women. Laboring women would be attended by midwives in temporary shelters in the fields, staying for a week (for a boy) or two weeks (for a girl). Afterward, mother and newborn would move to the beit niddah for an additional 33 or 66 days, respectively.

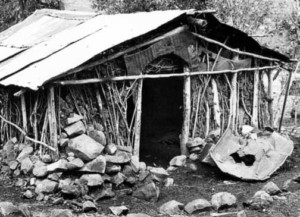

The beit niddah’s location varied – sometimes at the village outskirts, sometimes at its center. Its distinctive feature was a border of pebbles or low stones, setting it apart from other huts. Children could approach the border but were forbidden from entering or touching their mothers, highlighting the concept of ritual separation integral to this seven day spa tradition. Accidental contact required ritual immersion and waiting until nightfall to return home, underscoring the significance of purity.

The size of the beit niddah varied, accommodating anywhere from one to twenty women. While solitude was possible, communal beit niddahs fostered a unique form of female solidarity. As one kes described, “In a larger beit niddah all the women were together, talking with each other. They were alone… together.” This “alone together” aspect mirrors the communal experience sometimes found in modern wellness retreats and seven day spas, where individual rejuvenation occurs within a supportive group setting.

Days in the beit niddah were a period of respite. Women rested, slept, walked in fields, or by rivers. Forbidden from village interaction or entering homes, they were cared for by other women who brought food and water. Larger beit niddahs became spaces for intergenerational exchange, with women of all ages sharing stories, advice, and crafting together, often embroidering clothing and leaving their work to be continued on subsequent visits. Upon leaving this seven day spa equivalent, women immersed in the river, washed their garments, and returned home after nightfall, symbolically and physically cleansed.

Stories shared by informants painted a vivid picture of the beit niddah’s role in community life. One anecdote told of a wedding dress urgently brought to the beit niddah‘s periphery for embroidery, highlighting the community’s reliance on the skills and collective effort of women within this space. The celebration surrounding a girl’s first menstruation, marked by a family feast upon her return from her initial seven day spa experience in the beit niddah, further emphasized the significance of this rite of passage. “When a girl got her period for the first time, it was like when a woman gave birth for the first time. Everybody celebrated,” one woman recalled.

The beit niddah emerges as a distinct female sphere, a precursor to modern women’s wellness retreats. It fostered bonds, provided a space for mentorship between generations, and offered a week-long “Shabbat with the girls,” as one informant described it – a “no boys allowed” zone. The Hebrew terms “chevrah” (friendship group) and “bayit” (home) were used to convey the atmosphere and sense of belonging within the beit niddah, highlighting its role as both a social and personal sanctuary.

Women’s menstrual cycles, therefore, profoundly shaped village life. The public nature of the beit niddah and the shared awareness of women’s bodily status fostered an open and accepting attitude towards women’s bodies. Religious Ethiopian Israeli men and women spoke openly about menstruation, intimacy, and female bodies – topics often considered taboo in Western cultures – because these were integral and accepted aspects of their daily lives, regulated by traditions like the seven day spa of the beit niddah.

In Israel, the beit niddah underwent significant adaptations. In refugee centers, women improvised makeshift spaces at the ends of hallways. As they moved into caravans and apartments, closets and balconies became substitute huts. Even today, older religious Ethiopian Israeli women may refrain from cooking or entering kitchens during menstruation, echoing aspects of the traditional separation. Paradoxically, Israel’s 14-week paid maternity leave has allowed some women to observe modified postpartum practices, remaining in their bedrooms for extended periods, reminiscent of the beit niddah postpartum stay. Abstaining from synagogue visits during menstruation remains common, even among younger women, reflecting a continued adherence to certain purity concepts.

One particularly devout woman, Leah, the wife of a kes, initially refused to enter her home while menstruating, even in harsh weather. Government intervention and the construction of a dedicated beit niddah shed adjacent to her home in Hadera – reportedly the only full-fledged beit niddah in Israel – illustrate the tension between tradition and modern Israeli society. For Leah, these purity rituals are central to her Jewish identity, an unwavering commitment to Torah law.

Leah’s dedication has influenced her daughters, who, while embracing rabbinic law as religious Israelis, still grapple with their heritage. Leah’s married daughter observes rabbinic purity laws, using a mikveh and separating from her husband during menstruation. However, Leah finds rabbinic practices perplexing, questioning the cleanliness of a mikveh compared to a river and the permissibility of being in her house while menstruating. She herself only immerses in the Mediterranean Sea, maintaining a stricter interpretation of purification.

While most young religious Ethiopian Israelis accept rabbinic law, some, like Tamar, view it as an extension of their Ethiopian traditions, not a replacement. Tamar sees rabbinic law as “a continuation of what was in Ethiopia. Everything is one, but in Ethiopia it was stricter.” She acknowledges the beit niddah customs of her childhood but feels too young to have fully experienced them.

Ethiopian Israeli women in their twenties and thirties navigate a dual identity, bridging two worlds. They are actively engaged in re-evaluating their heritage, selectively preserving rituals while adapting to Israeli society. Some fully assimilate, while others maintain aspects of their Ethiopian culture, like speaking Amharic and baking injera. They embody the “alone… together” sentiment – navigating their unique experiences while connecting with both their ancestral past and their Israeli present. Tamar’s intention to “walk from both” traditions, studying rabbinic law while seeking guidance from her mother and aunt on traditional practices, exemplifies this nuanced approach to cultural integration.

Sarah Greenberg conducted her senior thesis at Yale on the evolving niddah practices within the Ethiopian Israeli community. She is currently pursuing graduate studies at Stern College.